Your Friendly Introduction to Music Theory

✨🎹✨ Here's an interactive introduction to music theory. Upon reading and

interacting with the information in this guide, you'll get a good general

overview of what music theory is and how all the pieces fit together to help

with music-making.

This guide assumes no prior music knowledge and aims to explain things in a

simple non-nonsense way that everyone who's motivated to learn can understand.

Ready, set, go! 💨

0. What is Music Theory?

To define what music theory is, let's first define music and theory:

Music

Music is a series of sounds (pitches) and silences (rests) organized over time.

Theory

Theory is a system that help us think about and analyze something.

Music Theory

So with that, we can see that music theory is nothing more than a system that help us think about and analyze the series of pitches and rests that make up music.

Music theory is not a set of 'rules', but rather a framework that makes it easier to understand how music works.

This framework in turn can become an invaluable tool to help us make music that sounds good to our ears and that evokes the desired emotions.

1. Notes

We defined music as a series of pitches and rests organized over time.

A system of 12 pitches has been created and this system gives us the 12 notes that we now use in Western music. These 12 notes are the basic building blocks of music.

1.1 Musical Alphabet

Out of the 12 notes in our musical system, 7 of them are known as natural notes and each of these natural notes are named after a letter of the alphabet. The 7 natural notes are: A B C D E F G.

Press on any of the note names below to hear the sound of that note on the piano:

1.2 Octave

There are 7 natural notes, but you might say "well there are more than 7 notes on the piano!?" What happens is that after every set of natural notes, the pitch is now double that of the first natural note, and our brain hears that as the same note again but on a higher register.

What that means in practice is that after our set of 7 natural notes, we start again with the same note names on a new 'level' that we call an octave. It's called an octave (octa meaning 8) because of the 7 natural notes plus 1 more note to start again.

Here's a full octave from A to A an octave higher:

Sometimes we want to know exactly which note A we're talking about, not just that's it's one of the A notes. Octaves are numbered, so we can specify exactly which one we're talking about. In the interactive example above, the first A is A3 and the 2nd one is A4.

1.3 Octaves change on C

So far we've been going through the musical alphabet from A to G, but actually we change octave number every time we reach a C note, so it's more common to think of the musical alphabet as starting from C and ending in B, to then start again at C.

Below you can play an octave from C to C and the octave number is included to illustrate the octave change:

1.4 Natural Notes on the piano

On a piano, the natural notes that form the musical alphabet are all the white keys with none of the black keys:

→ Notice how the C notes fall to the left of the set of two black keys.

→ On a full size piano, the note C that's roughly in the middle of the piano keyboard is known as middle C and represents the note C at the 4th octave (C4). Middle C is often a very good point of reference on the piano.

1.5 Sharp and Flat Notes

We talked about the 7 natural notes, but at the beginning of this section I said that there are 12 notes in our musical system. So what are the additional 5 notes then?

The remaining notes to complete our 12-note system have the same note letters, but are said to be either sharp or flat.

Sharp notes are noted with the ♯ symbol and flat notes are noted with the ♭ symbol. So, for example, after the natural note C comes C♯ or D♭.

These two note names, C♯ or D♭, are two names for the same note, and the name we use to talk about them often depends on context. If we're going up the notes of the piano, we'll often call it C♯ and if we're going down, we'll often call it D♭.

Here are the 5 notes that can be either sharp or flat, press to hear their pitch:

D♭

E♭

G♭

A♭

B♭

The sharp or flat notes are all the black keys on the piano, with none of the white keys:

1.6 Half steps (semitones) and whole steps

We often need to refer to the distance between notes in our 12-note musical system.

In order to do that we need a unit of measure. That unit of measure is called the half step (also known as semitone) or whole step (also known as whole tone). The distance between 2 adjacent notes is one half step, and the distance between 2 notes that have a note in between them is called a whole step.

Calculating distances like that in terms of half steps and whole steps, every note counts, including the sharp or flat notes.

For instance, the distance between C and C♯ is a half step and the distance between C and D is a whole step.

That was a lot! 😅 Congrats on making it this far. Now that you know about the musical notes, you can start exploring what we do with these notes to create music. 🎉

2. Scales

Now that we know about the 12 musical notes, 7 natural notes and 5 sharp or flat notes, let's talk about how they are used concretely in music.

Just like you wouldn't use every ingredient in your pantry in a single recipe, usually we don't use all 12 possible notes in a given piece of music.

Instead, we tend to roughly limit the notes we use to the notes in a chosen musical scale.

This way we can create music with a smaller subset of notes that are known to work well together.

A musical scale is the word we use to talk about a group of musical notes that are in ascending or descending order of pitch.

2.1 Chromatic Scale

The most fundamental scale is called the chromatic scale, which is just a fancy way of saying a scale that contains all 12 notes of our musical system.

Like I mentioned above, normally we don't use all 12 possible notes in a piece of music. For this reason, the chromatic scale is rarely used on it's own. The chromatic scale is instead just the basis upon which other scales are created.

2.2 Diatonic Scales

A diatonic scale is a 7-note scale formed with notes that are separated either by whole steps or half steps.

In a diatonic scale, 5 of the notes are a whole step apart and 2 of the notes are a half step apart. The 2 main types of diatonic scales are major scales and natural minor scales.

Diatonic scales are the main type of scale used in Western music.

2.3 Major Scales

Major scales are a type of diatonic scale that's formed with notes that are in this pattern of whole steps and half steps:

You can start on any of the 12 musical notes, and then pick notes that follow that pattern of whole steps and half steps and you'll have the major scale for that note.

What this means is that there are 12 possible major scales, one starting on each of the 12 possible notes.

Major scales are named by the starting note, called the root note of the scale. For example, a major scale starting on the note D is called a D major scale.

The easiest scale to remember is the C major scale, which is simply all the white notes on the piano, all natural notes with no sharps or flats:

Looking at the piano key configuration for the C major scale, we get a visual reminder of the pattern of whole steps and half steps that form the major scale:

C → D Whole

D → E half

E → F Whole

F → G Whole

G → A Whole

A → B half

B → C

Since the C major scale uses only the white keys, The set of 3 black keys followed by two white keys next to each other, then a set of 2 black keys create that pattern (Whole Whole Half Whole Whole Whole Half).

If you're playing notes on the piano and sticking to only the white notes, you're playing notes from the C major scale. Or, it could mean you're playing notes from the A natural minor scale, more on that later when we talk about relative minor.

Diatonic scales, which major scales are a part of, have 7 notes per scale, however the first note of the scale is often repeated to complete the octave. So 7-note scales will often be spelled out like this: G A B C D E F♯ G

Music based upon the notes of a major scale tends to sound happy and uplifting, however it's quite possible to make sad-sounding music using a major scale.

2.4 Natural Minor Scales

Natural minor scales, often just called minor scales, are a type of diatonic scale that's formed with notes that are in this pattern of whole steps and half steps:

There are 3 types of minor scales: natural minor, harmonic minor and melodic minor. The "default" one is the natural minor scale and when, for example, someone says the B minor scale, what is most often implied is the B natural minor scale.

Music based upon the notes of a minor scale tends to sound sad and moody, however it's quite possible to make happy-sounding music using a minor scale.

The easiest minor scale to remember is the A minor scale, which is also just the white keys on the piano:

But wait, what?! How can two scales one major and one minor use the same exact notes, you might wonder. The reason is that we start the scale on a different note. Read on to the following section to learn how that works...

2.5 Relative Minor & Major

Every major scale has a natural minor scale that has all the same notes, just played in a different order. Similarly, every natural minor scale has a major scale that has all the same notes, played in a different order. This is called a relative major or minor.

The reason why that works is that when we start a scale on a different note, we get a different order of half steps and whole steps in between the notes, and that creates a different sound for that scale.

You'll learn more about that in a following section when we talk about keys and tonal center.

An easy way to know which scale is a relative major or minor of a given scale is using the circle of fifths, which will be covered later in this guide.

For now, you can just keep in mind that every major and natural minor scale has relative scale of the opposite quality that contains the same notes, but played starting on a different note.

3. Intervals

Intervals are the gaps between notes.

They're the building blocks of harmony and the musical distance between two notes.

Understanding intervals helps you see how notes relate to one another, making it easier to harmonize, form chords and even create melodies!

3.1 Basics of Intervals

Every interval has a number and a quality, and this combo describes the relationship between two notes.

Number: Based on how many letter names (or scale degrees) it spans. For example, the interval from C to E spans C-D-E, which is three letter names. So, its number is a third.

Quality: Indicates the specific size of the interval. In music, we use the terms perfect, major, minor, augmented, and diminished to describe interval quality.

For instance, the interval from C to E in the C major scale is called a major third. If you move that E down to E♭, it becomes a minor third.

3.2 Common Intervals

- Unison: This is when two notes are the same. It's also called a "perfect unison."

- Second: The gap between two adjacent notes, like C to D.

- Third: Spanning three letter names. For instance, C to E.

- Fourth: Spanning four letter names, like C to F.

- Fifth: Spanning five letter names, for example, C to G.

- Sixth: An example is C to A.

- Seventh: C to B is a seventh.

- Octave: This is an interval spanning eight letter names. C to the next C is an octave.

3.3 Quality of Intervals

This is where the richness of music theory starts to shine!

- Perfect: Unison, fourth, fifth, and octave can be perfect. For instance, C to G is a perfect fifth.

- Major: Seconds, thirds, sixths, and sevenths can be major. C to E is a major third.

- Minor: Only seconds, thirds, sixths, and sevenths can be minor. C to E♭ is a minor third.

- Augmented: This is when you raise a perfect or a major interval by a half step. If you raise the G in a perfect fifth (C to G) to G♯, you get an augmented fifth (C to G♯).

- Diminished: When you lower a perfect or a minor interval by a half step. If you lower the fifth in a perfect fifth (C to G) to G♭, you get a diminished fifth (C to G♭).

3.4 Enharmonic Intervals

Sometimes, two different intervals can sound the same. These are called enharmonic intervals. For instance, an augmented fourth (C to F♯) sounds the same as a diminished fifth (C to G♭) on a piano, but they serve different functions in music and harmony.

3.5 Using Intervals in Music

Recognizing intervals can greatly aid in:

- Harmonizing: Sing or play a note, then harmonize using a third or a fifth above or below.

- Transposing: Shifting the entire set of notes in a piece up or down by a consistent interval.

- Composing: Intervals help in deciding which notes will sound good together, helping composers craft melodies and harmonies.

Woo! That's intervals for you. A crucial building block of music. When you start to recognize intervals by ear, you'll find it's like having a superpower. Music will never sound the same again! 🎶

➡️ Try out the piano interval tool to practice your interval recognition skills.

4. Chords

Chords are the harmonious pillars of music.

They're groups of notes played together, giving depth to melodies and forming the backbone of countless songs.

From the emotive ballad to the upbeat pop tune, chords bring feelings and richness to tunes.

4.1 What is a Chord?

A chord is a combination of three or more notes played simultaneously. The simplest type of chord is the triad, which consists of three notes. These three notes are the root, the third, and the fifth (remember intervals 😉).

4.2 Types of Chords

Triads: These are three-note chords and are the most fundamental. There are four primary types:

- Major Triad: Consists of a root, a major third, and a perfect fifth. For instance, C-E-G.

- Minor Triad: Contains a root, a minor third, and a perfect fifth. For example, C-E♭-G.

- Diminished Triad: Features a root, a minor third, and a diminished fifth. Like C-E♭-G♭.

- Augmented Triad: Has a root, a major third, and an augmented fifth. C-E-G♯ is an example.

Seventh Chords: These are four-note chords. Adding a seventh note to a triad creates these:

- Major 7th: A major triad plus a major seventh.

- Minor 7th: A minor triad followed by a minor seventh.

- Dominant 7th: A major triad plus a minor seventh.

- Half-Diminished: A diminished triad with a minor seventh.

4.3 Chord Inversions

When the notes of a chord are rearranged so that a note other than the root is the lowest note, we call this an inversion.

Inversions can provide smoother transitions between chords and give a different texture to the harmony.

For example:

- Root Position: The root is the lowest note. (C-E-G)

- 1st Inversion: The third is the lowest note. (E-G-C)

- 2nd Inversion: The fifth is the lowest note. (G-C-E)

4.4 Chord Progressions

A sequence of chords played in order creates a chord progression.

These progressions lay the groundwork for many songs. A classic example is the I-IV-V progression, which in the key of C would be C-F-G.

4.5 Using Chords in Music

Harmonization: Chords provide the harmonious background against which melodies shine.

Building Tension and Release: Certain chords build tension (like the dominant seventh) that is resolved with the return to a more stable chord, often the tonic.

Setting the Mood: The type of chord (major, minor, diminished) can set the entire mood of a song or section.

There you go, a whirlwind tour of chords!

They might seem complex at first, but once you start recognizing and playing them, you’ll discover the sheer magic they add to music. Dive in, experiment, and soon, you'll be weaving chords into your own musical narratives. 🎹🎵

➡️ Check out the piano chord tool for an interactive way to explore chords.

5. Keys, Key Signatures & The Circle of Fifths

Unlocking the secrets of keys, key signatures and the Circle of Fifths can transform how you view, compose, and perform music.

These concepts are foundational to understanding musical relationships and creating interesting chord progressions.

5.1 What is a Key?

Before delving into key signatures, it's crucial to grasp what a key means in music. Essentially, a key denotes the primary tonal center or the home note around which a piece of music revolves.

Tonal Center: When a song is in the "key of C Major," C is its foundational note or center.

Associated Scale: Every key aligns with a specific scale. If a song is in the key of G Major, it predominantly uses notes from the G Major scale.

5.2 Keys and Key Signatures

A key's associated scale naturally leads to its key signature.

For example, D Major's key has two sharps: F♯ and C♯. When you see these sharps in a key signature, it's an indication that the piece is in D Major.

In a nutshell, while scales give us a collection of notes, the key sets the primary note around which music is constructed. This foundation leads us to understand key signatures.

5.3 What is a Key Signature?

A key signature is a collection of sharp or flat symbols placed at the beginning of a piece of music in music notation, immediately after the clef.

It indicates which pitches should consistently be played as sharp or flat throughout the piece, simplifying the notation.

5.4 Understanding Major and Minor Keys

Every key signature corresponds to both a major or a minor key. For example, both C Major and A minor share the same key signature (no sharps or flats).

The major key usually sounds bright and upbeat, while its relative minor (using the same key signature) tends to sound more somber or serious.

5.5 The Circle of Fifths

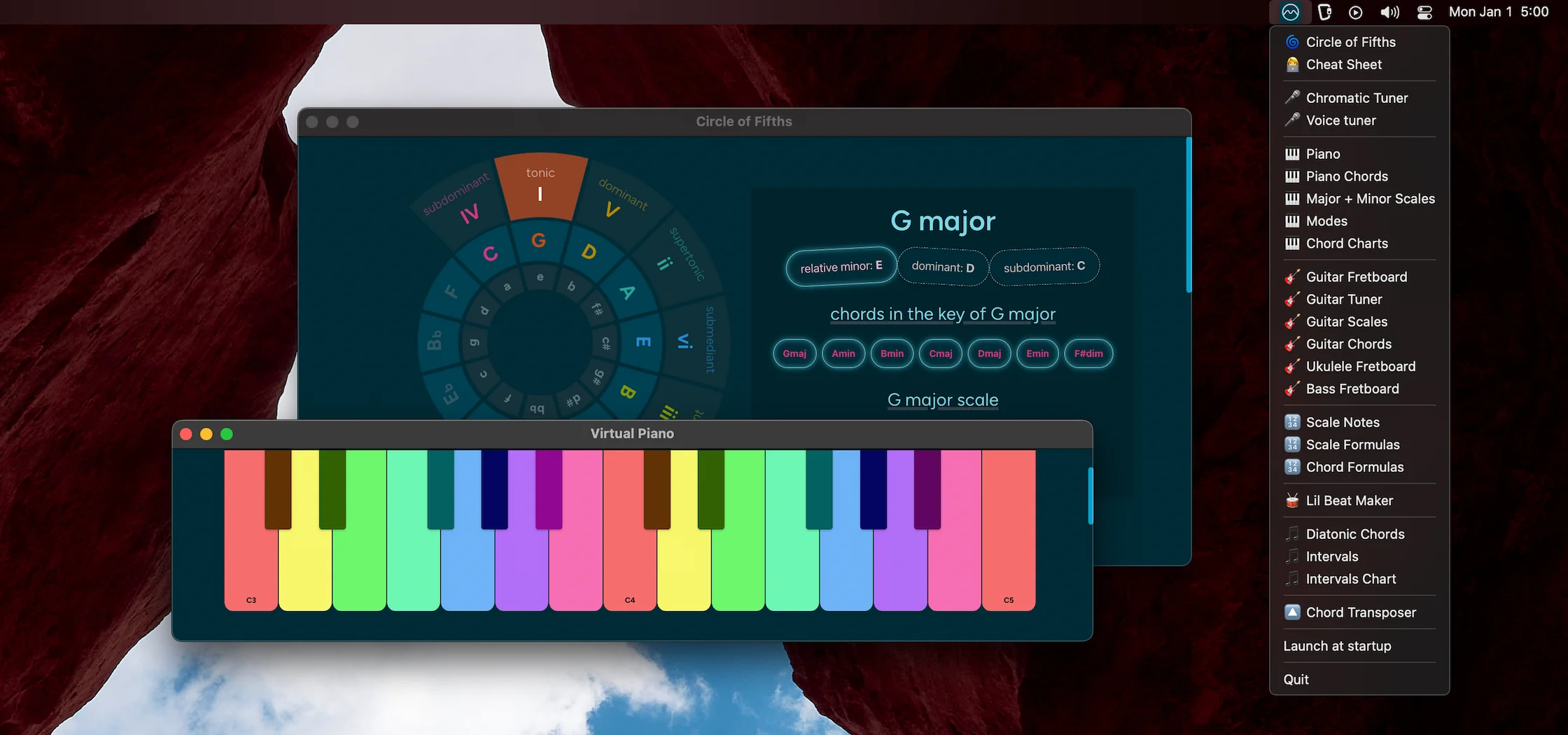

The circle of fifths is a fantastic tool for visualizing and understanding the relationship between different keys.

The Circle arranges the 12 keys (both major and minor) in a circle. Adjacent keys are a perfect fifth apart, hence the name.

The key signature is determined depending on how we navigate the circle of fifths:

- Clockwise: Moving in this direction, you add a sharp to the key signature.

- Counter-Clockwise: Moving this way, you add a flat.

Here's a circle of fifths, with major keys on the outer ring, minor keys on the inner ring, and the key signature of each key on the outside:

5.6 Benefits of the Circle of Fifths

- Predicting Chord Progressions: Musicians often move between chords that are close on the Circle of Fifths, making it a powerful tool for anticipating chord changes.

- Modulation: The Circle can guide composers and improvisers on smooth ways to transition between keys, a process known as modulation.

- Understanding Relationships: It visually showcases the relationship between major and minor keys and helps in understanding scales and chord formations in different keys.

5.7 Practical Uses

Musicians regularly employ the Circle of Fifths and key signatures in various ways:

- Composing: By understanding key relationships, composers can craft smooth transitions and engaging chord progressions.

- Transposing: Need to shift a piece of music into a different key? The Circle can guide the way.

- Improvising: For soloists, especially in jazz, the Circle can be a roadmap for navigating through chord changes.

Diving into key signatures and the Circle of Fifths is akin to acquiring a new lens to view the world of music.

With these tools in hand, you’ll find that the landscape of sound becomes more navigable, predictable, and even more exciting. 🎶🔑

6. Rhythm & Time Signatures

Rhythm is often described as the heartbeat or the timing of music.

Understanding rhythm is crucial, as it dictates when notes are played and for how long. Let's break this down.

6.1 Basic Rhythmic Values

- Whole Note (Semibreve): A note that lasts for four beats.

- Half Note (Minim): Worth two beats.

- Quarter Note (Crotchet): Equivalent to one beat.

- Eighth Note (Quaver): Half the duration of a quarter note, or half a beat.

- Sixteenth Note (Semiquaver): One quarter of a beat.

6.2 Rests

Just like we have notes of different lengths, we have corresponding rests, which indicate silences of various durations.

6.3 Time Signatures

A time signature sets the rhythm's structure, indicating the number of beats in a measure and the type of note that gets one beat.

Top Number: Tells us the number of beats in each measure.

Bottom Number: Indicates the type of note that counts as one beat.

For instance:

- 4/4 time (Common Time): Four beats in each measure, with a quarter note counting as one beat. It's the most widespread time signature.

- 3/4 time (Waltz Time): Three beats per measure, with a quarter note as one beat.

- 6/8 time: Six beats in every measure, but the beat is divided into two, with an eighth note as one beat. This gives it a 'lilting' or 'swaying' feel.

There's a lot more that goes into grasping rhythm in music, but now you know about some of the main building blocks.

By understanding these elements, you lay the foundation for rhythm in music, allowing compositions to come alive with dynamics and flow. 🎶🥁

7. Conclusion

Music's vibrant tapestry is made up of several intricate threads:

- Notes: The foundational sounds that start our musical journey.

- Intervals: Distances between notes that shape melodies.

- Chords: Harmonious blends that add depth and emotion.

- Scales & Keys: Maps of musical landscapes, guiding us in composition and understanding.

- Key Signatures & The Circle of Fifths: Unlocking the relationships and patterns in music.

- Rhythm & Time Signatures: The heartbeat of every piece, dictating flow and movement.

Remember:

- These elements form the DNA of every musical piece.

- Understanding them enriches your musical journey.

- They're tools for creation, expression, and connection.

With this foundation, you're set to explore, create, and truly experience music. 🎵🎶🎹🎸🎻